CSCI 491: Fukushima

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Japan caused the three operating nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant to automatically shut down. The earthquake damaged the power grid leading to Fukushima cutting the plant off of external power. Emergency diesel generators immediately kicked in to generate power to run the cooling machinery. 50 minutes after the generators started a 15-meter tsunami hit the 10-meter sea wall overwhelming the sea wall and flooded the diesel generators at the plant. These two natural disasters caused a complex cascade of failures making Fukushima the worst nuclear disaster.

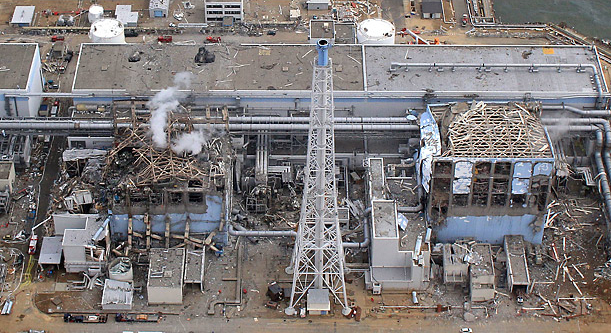

Following the natural disasters, the Fukushima power plant was isolated from the power grid, running low on emergency power, and inundated with seawater. Fukushima had been operating three reactors at near full power before the earthquake. After an emergency reactor shut down the reactor core still produces heat as fission products continue to decay. The decision was made to use firetrucks to pump water into the reactor cores to cool them. To allow firetrucks to pump water into the reactor cores, pressure must be vented from the cores, which requires the release of steam. However, since the reactors have not had adequate cooling hydrogen gas has formed within the core. Vented hydrogen gas caused an explosion at unit 1 and two explosions at unit 3. Further complicating the issue, an explosion and subsequent fire occurs above unit 4’s spent fuel pool. Spent fuel still generates heat and must be stored in pools that require constant cooling. The explosions and fire release high levels of radiation into the area surrounding the plant. Concern over potentially hazardous levels of radiation make it nearly impossible for workers to continue to try to bring the reactors to a stable state.

Interactive map of radiation release from Fukushima Daiichi

Fukushima is the most complex nuclear disaster in history involving 2 natural disasters, 6 nuclear power plants, and multiple spent fuel pools. Further, the Fukushima disaster played out with exceptional media coverage unlike the near total media blackout perpetrated by the Soviet Union during the Chernobyl disaster. The natural disasters compounded the difficulty of adequately responding to the disaster by disrupting transportation of resources vital to the emergency response. Studies prior to the disaster found that the measures taken to protect the safety systems at the Fukushima reactor were insufficient. Specifically, the sea wall could be overrun by a large tsunami, exactly the type that caused the nuclear disaster.

The Fukushima disaster could have easily been worse than Chernobyl. Thankfully, the design of the reactors at Fukushima was much more modern than the reactor that was used at Chernobyl. Many of the issues that caused a significant release of radiation at Chernobyl were prevented by the design of the reactors at Fukushima. The safety systems designed to prevent mass release of radiation functioned adequately despite a near complete loss of cooling for 3 of the 6 reactors. Fukushima is estimated to have only released one tenth the radiation that the Chernobyl disaster did. Fukushima was the first multiple unit nuclear disaster and generating a proactive response plan for a multiple unit failure was unheard of before the Fukushima disaster. Today, none of the reactors at the Fukushima complex produce power, a further departure from previous nuclear disasters. Three of the reactors experienced a core meltdown and the extent of the damage to the reactors still isn’t fully known.

Next week we will finally conclude this series on nuclear disasters and look at some theoretical designs that could make nuclear disasters impossible.